In 306 BCE a 35 year-old philosopher bought a piece of land to establish his own school just down the road from Plato’s thriving Academy, forty years after the old Plato passed away. Indeed, Plato might have rolled in his grave if he knew what Epicurus was teaching so close to home.

Plato teaches of a universal truth, higher forms of beauty in an immaterial world, of the human soul which mirrors this form in essence and the balance of virtue as a means to perfection. Epicurus begins with a compelling metaphysical take on philosophy from the well-developed atomist doctrine of his day: something cannot come from nothing, and nothing is ever destroyed. He goes on to build a theoretical physics system, all to the end of explaining away personal and collective fear of death and religion. Epicurean interest in science is purely therapeutic.

Epicurus draw incomplete conclusions about the substance of the good. To him, it all ends in the body. The soul, he insists, must be a thin substance that simply evaporates at the time of death. Epicurus’s disbelief is proof of the ideas that kept him up at night. His philosophy is inherently flawed with disbelief, but his school is important for other reasons. Unlike Plato’s Academy, the Garden of Epicurus was founded to welcome free men, women and slaves alike, an immersion of Eastern luxuries in conservative Athens. That’s the Epicurean philosophy. Friendship and equanimity between the sexes, detached parenting and politics. Hail prudence for cultivating a better peace of mind. He tells his friends that the gods were real, but religion has misrepresented them, much to the detriment of society. The substance of the good is pleasure, which means God is basically pleasure. So no matter what happens, don’t freak out. Learn to enjoy it. To Epicureans, not even science has a purpose, besides the little solace it brings in providing us this explanation and relieving us of the anxiety we feel toward the hereafter. As for the nature of creation, it’s all just one everlasting stew cut with the same few ingredients. That’s the philosophy of Epicurus.

The meaning of the old riddle, of a goddess stepping into the mind of a young poet, is all but lost:

Parmenides, young dreamer,

I, Lady Truth, will show you the two paths of life:

Either it is, and it is impossible for anything not to be, that’s the way of truth, or else it is not, and nothing can be, that’s the way of disbelief. For you cannot know what is not, that is impossible. For anything you can think of must be.

The atomist doctrine presumed an empty void through which tiny particles moved in space. The goddess of Parmenides challenged the distinction that mortals made between bodies and space. The one they call the “fire of heaven, light, thin in every direction the same as itself, but not the same as the other, the other being dark night, a compact and heavy body.” In a replete universe, this distinction is illusion. Both darkness and light coexist in and over every being at once. In a way, movement is an illusion, because the universe does not really change. Nothing ever was nor will ever be, because the universe is continuous being.

What’s so important about this?

Hundreds of years after his life and death, the philosophy of Epicurus was all the rage in imperial Rome. The freed slave, Epictetus, schools his wealthy young students against rampant Epicureanism in the capital. He lists the ways Epicurus has defaced the meaning of masculinity, turning bright academics into rebellious sons, unfaithful husbands, lazy fathers, spineless citizens and self-absorbed friends. A philosophy that deconstructs morality will ruin promising young men after all.

Just what we need to rationalize our wildest dreams!

No, wait— to rationalize our every whim and fancy!

Any desire we choose is good, so long as we judge it more pleasant than any unintended consequences. Happiness is the natural state, in the absence of pain.

Stoicism is less concerned with personal comfort. Epictetus refers to everything that is outside of our control as being “external.” Comfort is the ultimate example. Born a slave in Roman-occupied Phrygia and with his leg crippled from infancy, Epictetus lives with disability and discomfort. His philosophy is infused with politics deeper than the legal status of freedom. His physical disability gives him deeper insight into the Kingdom of Heaven.

Being denied the most basic dignity was not the end of Epictetus’s life. Raised in the court of Nero, he has witnessed far worse fate than being a lame old man. The ruling family of the first Roman imperial dynasty came to a violent end during his early years. Epictetus witnessed the collapse of the gens Claudia first hand. Child-emperors, groomed by family and country alike, to think of themselves as gods. What perfect tyranny, when the ruler exists not to rule but to be served and worshipped. Nature had not taught these men to rule like Caesar, because they had not had to rise through the ranks like Caesar. Nor had they followed the guidance of their tutors. They were ill-fated men from the start, desperate for an heir to throne. It was the avarice and pride of this family that Epictetus references to his students.

When you stand before one of those tyrants, just remember that he is the real tragic hero, not a staged actor, but the real Oedipus himself.

Everything external is outside our control, so don’t get attached to it. Yet people cling onto their stuff with all they’ve got. Jobs, furnitures, families. That’s the stuff of tragedies, people clinging onto what was never theirs to keep. To Stoics, virtue is the substance of the good. To Epictetus that means letting go of the idea that we deserve better. In order to be truly free we have to acknowledge what lies within our power. For what lies within our power is very thin: decency, trustworthiness and a sense of shame, but the fruit of our efforts is being in harmony with what God had in mind when he created the sexes. His most beautiful discourse IV.I On Freedom compares life to a traveler in the midst of a public festival.

Here is your one shot to ask questions, to find out what’s going on and enjoy the show. Give thanks for every minute, take care not to leave in disgrace. The stuff of tragedy is nascent in every man, woman and child, the selfish attachment at the root of every emotion. Jealousy, anger, fear. It is our basic instinct to cling onto the body, evidence of our intelligent design, yet the lowest part of us keeps the race. In truth each one of us is endowed with something far greater than atoms. We are like that riddle of Parmenides, substance and fire intertwined. The wisdom of Epictetus tells us that it is within our power to distinguish and seek light.

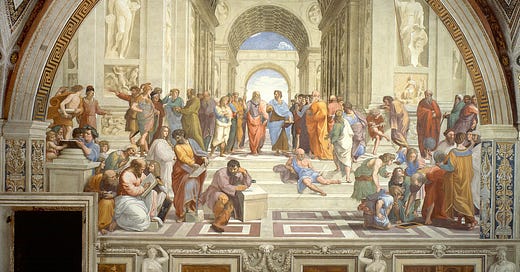

This emphasis on light is reminiscent of the ultimate Platonic allegory of the cave. We imagine the prisoners born at the bottom of a cave, enslaved not by iron but mental chains, the worship of idols— shaped by the hands of culture in our preference for tangible things. Only none of it is real. We think ourselves content with mere shadows, when behind us is a brighter world. Far from being old, dead white men, these ancient discourses animated the history of Western civilization and repeat themselves through the ages. Take the story of Einstein in his season of doubt.

I am at all events convinced that [God] does not play dice.

Einstein was not convinced when a young physicist by the name of Max Born presented his theory of quantum mechanics in 1926. The heart of this new theory is a principle of uncertainty which demonstrates the limit of our measurements. The idea of superposition implies that quantum systems can exist in multiple states simultaneously. For example, an electron might be in multiple energy levels or locations until it is measured, at which point it collapses into a single state. Reminiscent of Parmenides’ vision of a continuous universal being, light and dark coexisting at once in a replete universe, or a hologram of some purer realm of light. Einstein was led astray by a purely empirical, seeing-is-believing kind of philosophy, inspired by the 18th century Age of Enlightenment— an ironic return to ancient Epicureanism. In the end, the exception proves the rule. Fourteen months before his death he confesses to a friend, “if God created the world, his primary concern was certainly not to make its understanding easy for us.” The story of Moses is riddled with doubt.

Ancient philosophers, despite their profound insights, lacked the instrumentation to explore and measure the microscopic world as we understand it today. This forced even the most stubborn philosophers to assent to some speculative truth, like the presumption of void, empty space, waving their hand like a hypocrite to dismiss the possibility of that which can’t be seen or measured. What does it matter if the world is made up of tiny particles or not? What matters is the choice, the attitude of faith which asserts “it is” simply because it is impossible for anything not to be, the belief in the unseen that allows us make our way confidently through life. Where the sensualist of ancient days clings to the flesh, the empiricist clings to his devices blind to the true substance of the good, limited by the flaws of his perception. When such attitudes are taken for granted by the lazy academics of a new elite, they undermine the collective faith. Besides that, if it all comes down to “bodies and space” what’s the point in trying to unveil that final curtain? There’s no point if we already know the answer.

“There’s nothing there. We’re all just meat sacks, highly evolved apes, our consciousness evolved at random. We may as well just have a good time, have a few drinks and play some music.”

What greater things might you try if you put your faith in the truth, that we are no more bodies of flesh than we are bodies of light?

So what do you think, is Epicureanism the ancient “Liberal brain rot?”

Eric Vogelin identifies the "ecumenical empires" of the Axial Age as the origin-point of Manicheaism and Gnosticism. Magic, aka Hermeticism, was also endemic to the riverine civilizations of the Near East. All three of these ideas split the universe into good and evil, opposing and interacting forces, constituent elements. This is both necessary to invent skepticism and the scientific method AND the source of modern ideologies which engage in psychological splitting with scientistic pretensions. Humans are not as original as we like to think.

It sure looks like it from what you've written!